|

|

|

|

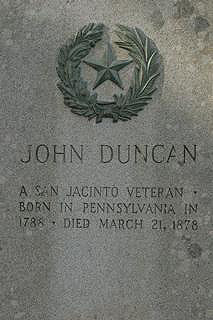

This cemetery is located on property once owned by John Duncan. There is a Texas Centennial marker located at the site. There are also slaves buried on the property, but the names are unknown. |

|

|

|

John Duncan

|

|

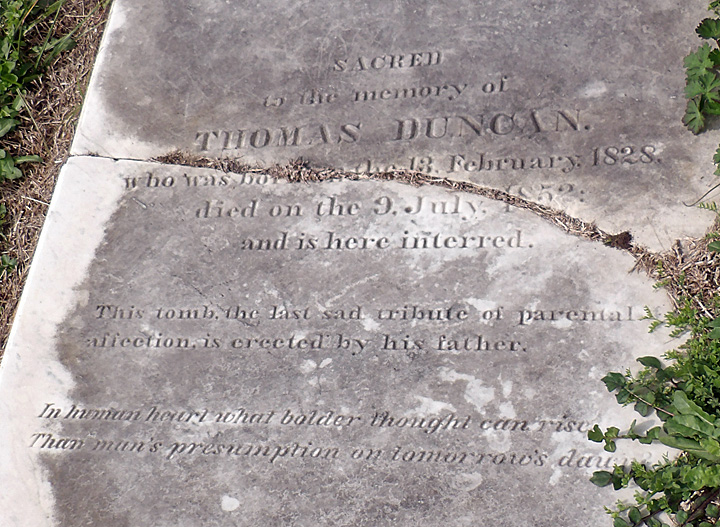

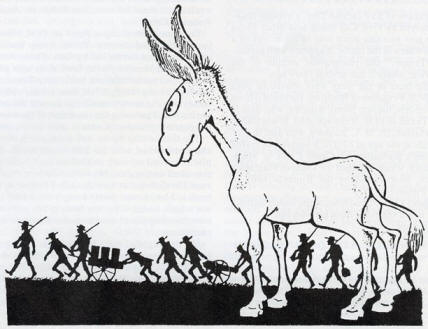

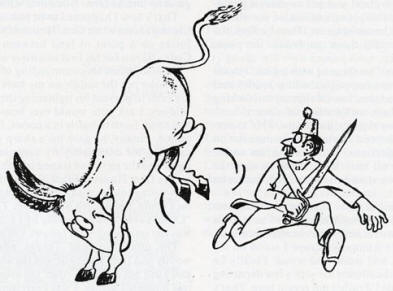

In many ways, Stephen F. Austin’s “Old Three Hundred” colonists can be likened in Texas history to the Pilgrims in the history of the United States. John Duncan was one of these historic settlers. Born in Pennsylvania in 1788, he first moved to Alabama and lived there until he was forty-five years old. He married Julia Coan of Gilford, Connecticut, born December 7, 1807. They were the parents of five children. For some unknown reason, John Duncan, who operated a successful line of steamships on the Alabama River between Catawbe, Mobile and Selma, abandoned his business, his plantation, and his family, and immigrated to Texas. He left Alabama in 1835 and upon arriving in Matagorda, enlisted in the Matagorda and Bay Prairie Company of Volunteers participating in the October 9, 1835, capture of Goliad under Captain George M. Collinsworth. Ten miles north of Bay City, bordering the meandering Caney Creek, in 1936, the state of Texas erected a marker commemorating John Duncan as an outstanding settler of early Texas. In 1835 Duncan was among the forty-nine signers of a pledge formulated to assure protection of the citizens of Goliad and all other towns they might enter. The citizens in return were to “stand firm to the Republic institutions of the government of Mexico and the State of Coahuila under the constitution of 1824. After they defeated the Mexicans at Goliad, the company disbanded; most of the men returned home. Duncan was also a member of the company dubbed “The Horse Marines.” This name was acquired when the company of twenty-five men under Captain Isaac W. Burton was assigned to guard four hundred miles of Texas coast. Upon discovering three Mexican ships offshore a few miles south of Matagorda, the men left their horses on the beach and piled into boats. They approached the enemy ships cheering and calling as in welcome. The Mexicans were duped for the trickery and were captured without firing a shot. Again in early 1836, Duncan became a member of the newly organized First Regiment of Texas Volunteers under Captain Moseley Baker, which prevented Santa Anna from crossing the Brazos at San Felipe for several days. Company D then moved on to San Jacinto and took part in the Battle of San Jacinto, which won Texas her freedom on April 21. It is said that Duncan became a hero in this battle for his charge in advance of the troops. The legend, however, has it that the mule Duncan was riding was accidently jabbed by the bayonet of a comrade, causing it to bold into action—followed by the rest of the startled company. Although John Duncan served as a private in the army, he was always known as “Captain Duncan” because of his early days as a steamboat captain. In 1837, with the Texas Revolution behind him, he accepted his league and labor of land in Matagorda County. He returned to Alabama, collected his family and his slaves and moved them to Texas. Duncan’s interests were not confined to Matagorda County, because deed records show him to have holdings in Comanche County also. John Duncan built a three-story home on the banks of Caney Creek but the only remaining landmark is a pair of giant crepe myrtle bushes. John and Julia Duncan’s children were: Thomas, born February 1828, in Alabama, and died July 9, 1852; Sarah, born 1834, in Alabama; John, Jr. “Jack,” born 1839, in Texas; Mary “Mollie,” born 1840, in Texas; and Samuel, born 1845, in Texas, and died February 26, 1853. Duncan was said to have owned ninety-four slaves in 1860. Their quarters were situated about one-half mile north of the home site; the brick cisterns were built from brick made on the plantation. One group of slaves was led by a tribal chief from Zululand named “Podo.” The tribe had been captured after being made drunk and hauled aboard ship in chains. The Kaffir slave was a leader for many years—even after they were free men and the plantation had been sold to A. H. “Shanghai” Pierce. The sugar cane producing area and the shipping switch on the Southern Pacific Railroad which ran through Duncan’s plantation, were known as “Podo.” The credit for founding the town of “Old Palacios” goes to Duncan, D. Davis D. Baker, and Isaac E. Robertson. This was a port on a tract of land between the Colorado and Tres Palacios Rivers which divided Matagorda and Tres Palacios Bays. It was destroyed by the storm of 1875. Most plantation owners of 1840 had some land in sugar cane. Duncan used his mechanical skill and put two steam engines into operation, one of them furnishing power for his sugar mill. Only fifty of his 13,000 acres were planted with cane in 1844, but he still out produced all his neighbors. John Duncan, Jr., was the only one of Duncan’s children to survive to full adulthood. Julia, their mother, died May 3, 1846, and her body was taken back to Mobile, Alabama. John’s will was probated May 8, 1878. When the Civil War ended and the slaves were freed, most of the plantation owners turned to cattle to try to recoup their lost fortunes. In 1850 there were 35,009 head of cattle in Matagorda County. All but nine farmers owned cattle. John Duncan had the largest herd—3,000 head. By 1870 the largest rancher was Abel Head “Shanghai” Pierce with about 35,000 head—one-half of the cattle population in the county. John Duncan had 5,000.

Historic Matagorda County, Volume I, pages

64-65 |

|

|

Died--In this city, on Friday the 9th instant, Thomas Duncan, eldest son of Capt. John Duncan, in the 24th year of his age. In expressing our deep regret at this afflictive dispensation of Divine Providence, we only give utterance to the sentiments and feelings of this whole community. The deceased has been a citizen of this State for the past ten or twelve years, having removed hither from Mobile (Ala.) his place of nativity. By his honorable and truthful character, he had secured the love and esteem of all who knew him. His death, cutting him off as it has, in the dawn of manhood, has produced a deep sensation in the wide circle of his friends and acquaintances. His disease, which was a subacute inflammation of the liver, was three weeks in running its course, but did not threaten a fatal termination until within the last week, and even strong hopes of his recovery were entertained by his friends until within the last four days.; Having, at his desire, on the night previous to his decease, received holy baptism at the hands of the Episcopal clergyman, Rev. H. N. Pierce, he expired about 9 o'clock on Friday night, trusting in God, and in charity with the world. May God heal the wound thus made, and soothe the sorrows of the bereaved and mourning family. The funeral, to which the public are invited, will take place this evening (Saturday, 10th) at 5 o'clock, from the Episcopal church. As Mr. Duncan was a member of the Masonic Lodge, he will be buried with Masonic ceremonies as well as those of the Episcopal church. Colorado Tribune, July 12, 1852

|

|

|

|

|

Brick Cistern |

|

Cane Syrup Kettle |

|

Duncan Property |

|