|

William Charles

"Chick" Clymer Jr. He was gone before I was a

teenager. Even so, I remember some things

about him. Chick (January 10, 1887 - November 21, 1847) was the brother of my grandfather Ray Clymer (Dada) and my great-uncle Albert Clymer. A thin, red-faced man, Chick lived at 931 West Morton Street, in the house that belonged to his mother, Grandma Clymer (Annie Ellen Schuel Clymer, a whole other story).

Chick’s large Adam’s apple

bobbed prominently in his long, thin neck. The

mottled red skin of that neck bore some

resemblance to the exterior of a plucked hen.

Such knowledge was not as unusual in a child

at that time as it would be now. Besides, the

Clymer family’s business was the Denison Poultry and

Egg Company, and the men of the family

all worked there at one time or another. As a

child doted upon by her grandfather, I used to

spend considerable time in the DP&E

office, allowed to peck undisturbed on the

typewriter keys with one finger or experiment

with the noisy adding machines. To me, “Freddy

the Fryer,” a DP&E brand name, was a

character as familiar as Porky Pig, Mr. Magoo,

or Woody Woodpecker. This was a family where,

when you knocked on someone’s front door, it

would be opened cheerfully with the greeting,

“Come on in! There’s nobody here but us

chickens.” Limp, plucked chickens were not a

novelty in the homes of my relatives. Chick’s niece Anne Goddard, her whole grown life, used to recall his nasal, nosed-wrinkled parody of Grandma Clymer's nagging: "Yänh, yänh, yänh, yänh, yänh."

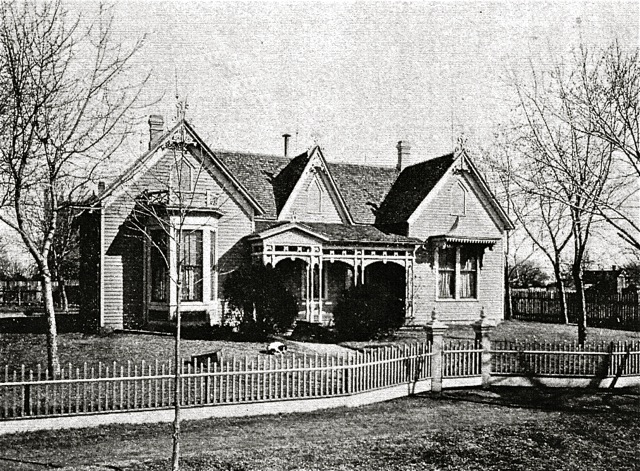

The house at 931 West Morton

Street was old, big, and two stories tall, but

Chick occupied a small narrow room on the

ground floor, right in the middle of all the

action, and close to the front door. His room

was filled almost entirely by two objects,

standing parallel and side by side: an upright

piano and a single bed. There was a small

aisle between them. Chick played ragtime tunes

on the piano at all hours. I used to think that Chick

had never married, but after I was grown I

came across evidence in an old Denison city

directory to the effect that, at one time, he

indeed had had a wife - briefly, I

gathered. And he had had a real estate company

on Rusk Avenue, posting a sign that read:

“Best Land A Crow Ever Flew Over.” To others, the central fact

about Chick was that he drank. That is, he got

drunk. A lot. When drunk, among other things,

he would drive his small old black Ford around

Denison dangerously. Sometimes he would hitch

a ride on others' cars, standing on the

running board the whole way. Upon arriving, he

would lightly hop off, call out "Thank ya,"

and weave away. Chick owned a small house

outside town on the old road to the Rod and Gun Club (now

the Denison Country Club).

One

time,

after my grandfather married his second wife,

Irma, and they moved into the big fancy house

with elaborate gingerbread trim at 1200 West

Morton Street, Chick tethered his goat to a

slender tree in the front yard there. It

stayed there for a couple of weeks and ate a

big circle in the grass around the tree. We

always went to Dada and Irma's house for

Sunday dinner after church, so I was able to

spend some time with the goat in the front

yard and observe minutely how the circle in

the grass grew as the grownups lengthened the

rope a little each day. My great-grandparents, Mama

and Papa White, who lived at 1013 West Bond

Street, were the parents of Dada's first wife.

That wife, the first Mavis, died when my

mother Mavis was about ten years old. (That

latter fact was why Dada, my mother, Aunt

Anne, and Uncle Ray lived with Grandma Clymer,

Chick, and Albert's family in the big house at

929 West Morton Street all during the

Depression.) Mama White used to serve big

meals at lunch even during the week, sometimes

inviting me with my mother and others to join

her and Papa White for such regular fare as

mashed potatoes, boiled green beans, chicken

and dumplings, fresh rolls, peach cobbler, and

other old-fashioned dishes—food for which I

must say I never have felt any great nostalgic

longing. Their dining room was furnished in

Mission oak. Sometimes they invited Chick to

join us. I remember one day at lunch

at Mama and Papa White's house, Chick was

telling a story and offhandedly remarked,

"Now, when I was a little girl, it wasn't like

that." My ears pricked up. "Uncle Chick, you

were never a little girl!" I protested. "Oh, yes, I was," he

insisted. Being of an age when I had

just gotten all this gender stuff down pat, I

went for the bait. "Uncle Chick, you were not!

"Well, I will tell you," he

said with utmost explanatory seriousness. "I

kissed my elbow and that made me turn into a

boy." The grownups had begun to snicker. "What?" I asked

incredulously. "Yes. If you are a girl and

you kiss your elbow, you will turn into a boy.

That's what I did. It works." Then he added,

"Try it. You can turn into a boy, too." Right

there at the table, I tried to kiss my elbow.

But I couldn't get my mouth that far down my

arm. "Don't worry," said Chick. "Just keep

practicing." For the next few weeks, I

practiced night and day. I thought that, if I

underwent sufficiently rigorous and dedicated

practice, eventually I would be able to get my

mouth to the end of my arm and I would turn

into a boy. But, to my sorrow, I never

succeeded. Thus I had to content myself with

living as a female member of the human race.

Only later did I get the joke. Note:

Aunt Anne says that Grandma Clymer had a

photograph of Anne’s father, Ray Clymer Sr.,

as a child, wearing long curls and a fancy

suit. The photo was kept in a closet. Once

Anne, then a child, came across the picture

and said to her father, “You look like a

little girl in this picture.” Dada replied, “I was one. But I kissed my elbow and changed into a boy.” Anne,

too, did elaborate exercises trying to

accomplish the impossible. by

Mavis Anne Bryant Biography Index Susan Hawkins ©2025 If you find any of Grayson County TXGenWeb links inoperable, please send me a message. |