|

|

|

The modern delta of the Colorado River is unique among Gulf Coastal Plain deltas in the remarkable speed with which it was deposited. Rapid deltation was caused by the removal of a log jam, or raft, that choked the river from its mouth to a point 46 miles upstream. The earliest recorded survey of the delta was made in 1908 when it encompassed about 45 acres. Removal of the raft began in 1925, and by 1929 a pilot channel was completed through the floating logs. Later that year a flood swept much of the raft materials and the impounded sediments into Matagorda Bay. Rapid deltaic growth resulted, and by 1930 the delta covered 1,780 acres. By 1936 the delta had extended itself across the bay to Matagorda Peninsula. In 1941 the delta attained an area of 7,098 acres. This was an increase of 160 times in just 33 years. Earlier river channels of the Colorado River are known. One flowed into Matagorda Bay in the vicinity of Tres Palacios Creek. The other flowed, together with the Brazos River into a large bay that occupied eastern Matagorda and western Brazoria Counties, Texas. Extensive deposition by these two rivers filled this bay, after which a delta was built into the Gulf of Mexico in the vicinity of Freeport. Any barrier beaches that may have existed in front of the bay were buried by deltaic sediments. Growth of the Colorado River The earliest known detailed map of the modern delta was made in 1908 when the delta encompassed some 45 acres. The next survey was made in 1930, one year after the 1929 flood, and showed that the delta had increased to 1,780 acres. In 1934, a discharge channel was dredged through the expanding new delta into the bay. The river was rejuvenating itself upstream, cutting new meanders and in places widening itself as much as 200 feet. This caused tons of sediments to be dumped into Matagorda Bay each day which made it impractical to maintain a flood channel through the delta even by constant dredging. The problem was not solved until 1935 when a foot of the delta, nearly a mile wide, finally reached across Matagorda Bay to Matagorda Peninsula. A channel was dredged across the delta and Through the offshore bar in 1936 and the Colorado River was forced to deposit its sediment directly into the Gulf of Mexico. River rises after 1936 caused some spillage out of the new channel into the bay, but by 1941 most of these outlets had been sealed. From 1929 to 1941 the delta grew at an average rate of about 500 acres per year. Virtually all delta building in the bay had ceased by 1941. The U. S. Army Corps of Engineers has maintained almost constant surveillance of conditions at the mouth of the Colorado River for over thirty years. They have accumulated much data that would be invaluable to geologists in studying this delta. Research on this paper was done in 1940 and 1941, and, like most geological papers or reports, this one represents conditions as they were thought to exist at that time. Since then the Engineers have constructed locks in the Intracoastal Canal on each side of the river after borings were made. Much maintenance work has been done in the river channel where it cuts through the delta. A preliminary examination of the Colorado River, Texas, by the United States Corps of Engineers. John C. Oakes, Captain, Corps of Engineers, filed the following report dated October 21, 1907, with United States Engineer Office, Galveston, Texas. SIR: In compliance with your instructions, I have the honor to submit the following report of a preliminary examination of the "Colorado River, with a view to obtaining a navigable channel from its mouth as far up as practicable." Numerous reports have been made covering conditions in the lower stretch of the river and Matagorda Bay. Attention is respectfully invited to the following reports for description of conditions. viz: Survey, Matagorda Bay at the mouth of St. Marys Bayou, near the town of Matagorda, Tex. Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers, page 1493, Part 2, 1882. Preliminary examination, Colorado River, Texas, with a view of removing raft at mouth of same. Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers, page 1939, Part 3, 1891. Preliminary examination, Colorado River, from the mouth to the city of Wharton. Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers, page 1821, Part 3, 1895. Preliminary examination, Colorado River, Texas, from its mouth to the foot of the great raft. Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers, page 2458, Part 4, 1900. Preliminary examination, Matagorda Bay, Texas, with a view to obtain a channel to Matagorda. House Document 154, Fifty-ninth Congress, first session. In general, it may be stated that the conditions and objections to the improvement set forth in the above reports exist today, except that the raft has been gradually growing upstream until it now extends, more or less continuously in the old river bed, some 20 or 25 miles. New channels have been cut out and in at various points for the flood waters, and in times of great floods the country adjacent to the river is overflowed. This last condition is being provided for by the construction of levees, and it is probable that within the next few years nearly the whole stretch of the river from Wharton to within a few miles of Matagorda will be leveed. To get into the river from deep water in Matagorda Bay would require some two or three miles of dredging, depending upon the depth of channel decided upon, and said channel would be very difficult to maintain under present conditions, owing to the immense amount of silt and snags that are brought in with each flood. To remove the raft in the river, even as far as Bay City, would cost a large sum of money, and it is a question if a canal could not be dredged alongside of the river for approximately the same cost as would be required for removing the raft. There is no commerce to speak of below Bay City, and that of Bay City is almost wholly due to the rice industry. During the last few years a great growth has taken place in this industry in Matagorda County, and it is stated that there are now some 60,000 acres of land in rice this year. In the vicinity of Bay City there are eleven pumping plants, taking water from the Colorado River, and these plants represent probably an average investment of $200,000. The rice interests desire that the river be not improved, because the rafts act to a certain extent as dams, and create storage reservoirs, holding back the water which is needed for irrigation in the dry season. Those interests fear that if these rafts should be removed, in very dry time, when most water is needed, there will not be sufficient water for their purposes. I believe their fears are well grounded. In any case the removal of the rafts would increase materially the height necessary to pump the water at each one of the plants, and would necessitate additional investment for improvements to comply with the changed conditions. There is not in my opinion sufficient commerce present or in sight above Bay City to warrant improvement beyond that point. In view of the above facts I respectfully recommend this river be considered for the present as unworthy of improvement by the General Government.

The above study of the Colorado River, which was completed in November of 1908, showed (probably the only time in the history of the raft) that there were persons who felt the raft was beneficial and those individuals were the rice farmers in Matagorda County. The rafts in the river caused the water to spread out and rice was irrigated by the use of gravity canals especially on the west side of the river. The gravity canal was engineered in such a manner as to be downhill all the way and was controlled by water boxes (water gates), flumes, and checks, which channeled water into the intake of the gravity system. This was effective until the reclamation districts completed the clearing of a channel along the east side of the raft for 45 miles in 1928. This caused an outlet, and as a result the gravity system of irrigation was no longer possible. As a result of this channel opening up the flow of water in the Colorado and an unusually dry period in 1928; rice crops were suffering for water. The farming and business interests of Matagorda County decided to solve the problem by sinking a dredge boat in the river, driving piling and covering it with a sack dam in an effort to divert water into the gravity system. Farmers with their field hands all cooperated in construction of this project. This dam was above Bay City and near the Wharton County line. Wharton County citizens complained because of fear of flooding their land. The Texas Rangers were soon called into the controversy. Since the site of the dam was somewhat inaccessible, it had to be approached from the north. An army-type field phone line was installed and a watchman was placed on the road to warn workers on the dam of the approach of the authorities. When the officers of the law arrived, the great majority of the dam builders had hidden in the underbrush, leaving a few workers to be arrested and taken into jail. The men taken to jail were quickly bailed out and were soon back working on the dam. This effort to save the 1928 rice crop was ineffective and failed. There was no rice crop on the west side of the river in 1929, as a flood washed out the raft completely, and the river dug a deep channel which required the construction of pumping plants (lift pumps) to raise water into the canals. The construction costs of the levees on the Colorado River near Bay City were paid from funds through the Reclamation District. Surplus monies were used later to build the protection levee around Matagorda. The closing story about the Colorado River in Matagorda County is the special report on "The Jetties" from the Daily Tribune, July 1, 1984

37 MILLION PROJECT REALIZATION OF A DREAM MOUTH OF THE COLORADO-It was a victory party years in the making, yet it wasn't particularly breath-taking and certainly wasn't fancy. What it was a modest joint patting on the back for the realization of a dream that touched five decades. More than 100 people, some of whom had watched the agonizingly slow process since Harry S. Truman was president, gathered Friday on the delta of the Colorado, between the river and the Gulf of Mexico, to mark the beginning of construction on the jetties project. ... For a number of years, startup on the Mouth of the Colorado River Project, usually called the jetties project, has flirted with Matagorda County supporters who have been time and again disappointed by a variety of roadblocks. In the spring of 1983, it was announced that the U. S. Corps of Engineers had found some money that would be earmarked to begin the $37 million undertaking. In December, a contract was awarded for the jetties construction. Still, many doubted the oft-delayed project would ever really get started. But now the huge rocks that will make up the jetties are being set in place and, as County Judge Burt O'Connell exclaimed, "I've stood on them, it's a reality." Army district engineer, Colonel Alan Laubscher outlined the project, telling the crowd that the jetty construction is scheduled for completion in September 1986 and then added that "Depending upon future congressional appropriations, construction of the diversion channel, diversion dam and navigation channel connecting to the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway will begin in mid-1986, with completion in the spring of 1989." Recreational features will get underway in late 1986, he said, to be completed in late 1987. Dredging of the jetty entrance channel and impoundment basin and turning basin is to start about October 1986 and the fish and wildlife features will get started in 1987. Overall completion is set for 1989.

The project consists of a jettied entrance

channel 15 feet deep and 200 feet wide, Laubscher explained. The

north jetty, which is east of the mouth of the river, will have a

length of 2,650 feet, including a 1,000 foot weir-where the jetty

will drop to a point where it will usually be below sea level. The

jetty west of the river will have a length of 1,450 feet. The

purpose of the jetties is to protect the mouth of the river from

silt buildup that hampers shipping. The project also includes a 20-foot by 250-foot diversion channel to move water from the river into West Matagorda Bay, supplying the beneficial nutrients to the marine life in the bay. Among the recreational features scheduled for the project are an elevated walkway along the north jetties for fishermen to reach the portion of the jetty beyond the weir, as well as boat launching ramps, parking areas, camping areas, and comfort stations. So, a new chapter on the river is being written as the Colorado Jetties Project is underway in 1986. In 1985 the Tribune editor said, "With an overall benefit-cost ratio estimated at about 6.4 to 1, it might be safe to say that Matagorda will regain some of its former prominence in the county."

Ironically, locomotives and large freighters will

not be paving the way to prosperity, as the 1888 editor

STRANGER THINGS HAVE HAPPENED!" |

|

By Fred S. Robbins Editor’s Note: Fred S. Robbins is one of the county’s oldest citizens. He has spent his life on or near the mouth of the Colorado River and has watched its numerous changes, not only as an interested citizen, but in the capacity of civil engineer. He is at the present time one of the three members of the Matagorda County Conservation and Reclamation Board, which board has charge of all matters pertaining to the river channel, and its present condition, and of that which may be its future. The river is still a serious problem and has reached that state when it can with all candor be called a United States government charge. The condition of the river at its mouth at Matagorda is bad and a constant threat to every part of the three coastal counties through which the stream makes it way, Matagorda, Wharton and Colorado. Should another raft form in the river, beginning at Matagorda, it will build up more rapidly than it ever has, and, the next one will have to stay, because the three counties will never again be able to raise sufficient funds to keep the stream clear. As stated, the mouth of this great stream at Matagorda is a government job and the people all along the stream should at once and of one accord put themselves squarely back of Congressman J. J. Mansfield and second his every move to convince the government of the immediate necessity for a deep channel to deep water, in the gulf, which engineers tell us will keep the stream clear for all time to come. Read Mr. Robbins’ comments which follow: Raft in the Colorado River In March of 1867, the “raft” began to form at the mouth of the west branch of the Colorado River, caused by logs and trees too large to pass out through the shallow water where the river flowed into Matagorda Bay, this raft formed rapidly up stream in the west branch of the Colorado River, but never formed rapidly up stream in the west branch of the Colorado River, but never formed in the east branch, so that while the west branch was closed, the mouth and for seven miles up stream, the east branch was never closed with the raft; but the east branch cut across into Saint Mary’s Bayou at the town of Matagorda and formed a new mouth for the east branch into Matagorda Bay, about two miles northeast of the old mouth, shortening this branch of the river about that distance, this part of the river, which was about 300 or 400 feet in width, gradually filled with silt and rushes, and a few logs, but a channel was cut through this in 1925-26 by the Matagorda County Conservation and Reclamation District but has remained without increasing as the Saint Mary’s Bayou channel had become the main mouth of the Colorado River. The raft in the west branch continued to form up stream and passed the upper end of the east branch, at the head of a large island known as Selkirk Island and continued to a distance of about 40 more further, or 47 miles from the mouth of the river, this raft formed solid, but after years, it piled up making sections of raft, and spaces of open river. As the raft built, the silt would settle in large quantities and for various distances, and depths, up stream preceding the raft, the drift piled up by the high waters pressed down heavily on this silt lying between each bank, and the bottom of the river, forming a firm foundation, like quicksand as long as it is firmly held in place, knowing this fact, a little dynamite was placed along a line near the middle of this raft, beginning at the lower end and a small “pilot ditch” was blown open, and when the current of the high water overflows came it washed this silt out from under the raft, which tore loose at each ban, broke up and washed out into Matagorda Bay, filling the bay and forming land, with thick growth of willow trees and rushes also mud flats nearly across the bay, probably a thousand acres or more, making it necessary to keep busy a large dredge boat, built and operated by the Matagorda County Conservation and Reclamation District in keeping open a channel from the mouth of the river through this immense quantity of silt and logs to Matagorda Bay, for navigation between the bay and the river, and to prevent another raft from forming at this mouth of the river and extending up stream as the former one did. Without an estimate of the immense quantity of silt, logs and debris, an idea might be partially imagined from the large acreage formed in the bay of Matagorda as above described. The Wharton County Conservation and Reclamation District No. 1 opened up the raft in Wharton County and in the northern part of Matagorda County, this was done by use of dredge boat, and heavy winches on barges and tractor work along the banks of the river, and some dynamite. The growing trees along the river banks, the length of the raft, were cleared away for a width of 30 feet on each side, to prevent timber getting into the river and forming more raft. A channel of “pilot ditch” was cut through this raft, the silt washed from under the raft broke to pieces from the banks, and washed out into the bay same as the lower part did when released by dynamite applied by the Matagorda County Conservation and Reclamation District No. 1, these two districts worked together as it was really one proposition and each depending on the other. In addition to work in the river freeing the raft, and cutting channels in the lower part of the river, the Matagorda County Conservation and Reclamation District, did many miles of large levee repairing and building on each side of the river, reclaiming many acres of land from overflow in times of high floods. In these processes the main channel of the river was followed most of the way, but in some instances in the lower portion of the river the water left the old channel and cut a large river around through bayous and sloughs paralleling the river, one most notable instance is that of the “Kate Ward Chute,” which was a ditch dug by slaves before the emancipation by the Civil War, which has now become the main river at this place. This raft was formed without any human agency, when, and as heretofore described. The wood-material of the raft was large cottonwood trees and many other varieties, as grow along the river banks, some cedar, red and mountain cedar, many posts, rails, cedar logs some mountain cedar railway ties, also some pine timbers bridges, etc., washed out along the water courses of the Colorado River and its tributaries. This was an independent raft, not caused by any other obstruction, but a natural phenomena, and caused by the shallow water at the mouth (or disemboguing) of the west branch of the river. In, or about 1868 or 1869, a chain was placed across the river about two miles above the mouth but the logs that floated this chain soon sank, and no raft ever reached this chain, so this chain caused no obstruction, whatever, but lies sunken in the river. There may have been other rafts in the river centuries ago as for an instance the field notes of the Selkirk Island survey, in 1824, call to begin as a small raft. Many years ago, a few small boats navigated the Colorado River as far up as Wharton and Columbus, carrying some small quantity of freight, but navigation was never put to practical use. In 1908, under the bridge across the Colorado River, near Bay City, the distance from the bridge down to the raft in the river was about 7 feet in 1931 after the river had been cleared of the raft, this distance instead of 7 feet was 52 feet from the bridge to the bottom of river, showing a washout of about 45 feet, thus the bottom of the river has been restored and a large carrying capacity and velocity, given to the river which has immensely relieved the overflowing condition. A large quantity of sand and silt, as well as drift wood, continue to come down the river and lodge in Matagorda Bay and requires constant attention, some places along the river, the banks are overflowed in flood times, and large quantities of sand built up or filled in several feet in depth. Many strange phenomena or freaks happen along this river, some surprising, and almost unaccountable. Matagorda County Tribune, Thursday, August 3, 1933 [From the archives of Haskell L. Simon with assistance of Jennifer Bishop, Mary B. McAllister Ingram Archives at the Matagorda County Museum.]

|

|

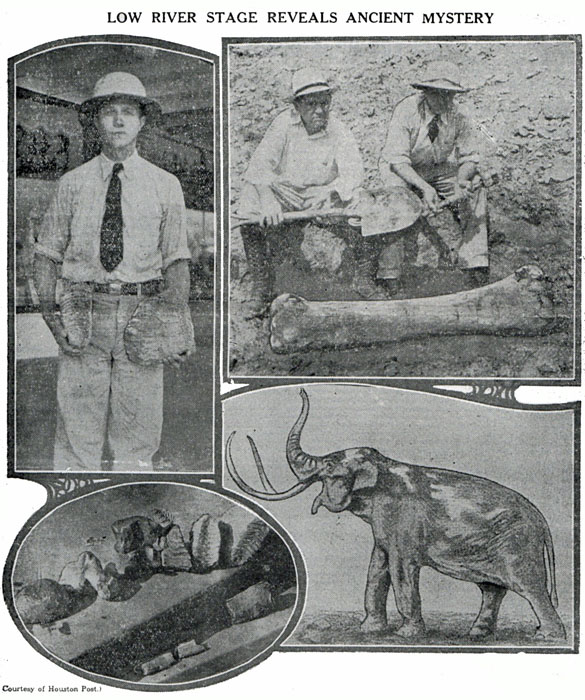

Million-Dollar Drouth Leads To Discovery Of Mastodon Near Bay City By Ed Kilman, Houston Post Down through the ages the rolling Colorado River has guarded a secret, locked within its watery bosom, of a strange era of strange beings that lived in this land when it was a different planet. And then, its waters parting as though in mystic revelation, the river last week divulged that hidden record of the unfathomed past, written in its quagmire sands thousands or hundreds of thousands of years ago. The Texas stream recently reached its lowest stage within the memory of man, and evidently the lowest since the morning of the world. And in the ooze of its uncovered bed, about two miles west of Bay City, there have been discovered the remains of an enormous mammoth or mastodon, which bogged there and thus sank into a state of partial preservation, finally yielding to the new age a token of the dark and unknown old. Double Size of Elephant Judging from the size of the bones, tusks and teeth, those who have examined them estimate that the beast must have stood 20 feet high and 30 feet in length from trunk to tail—nearly twice the size of the present-day elephant. That such monsters once gambled over the gulf coast country is already known to science, from other fossil relics that have been unearthed in the past. But the mystery of their appearance and disappearance upon these scenes has never yet been solved. Vague hints may be interpreted from some of the ageless traditions of the Indians, handed down through countless generations; but most likely these antediluvian mammoths lived and died in their epoch before the Red Man came. One of the most curious phenomena of the Bay City find was that the bones, when dug out of the mire, gave forth a distinct putrid odor, and black veins or nerve networks like plant root systems, were found clinging to all the bones. Moreover, the soil around the bones was of distinctly different colors from the surrounding yellow sand; in spots bearing a light gray hue, and in others a reddish brown such as the books say marked the hair of the prehistoric behemoth. Thus it seemed that a vestige of the flesh still clung to the skeleton through all the eons, so well was it preserved and sealed from air by the water and mud. Bones Crumbled Upon exposure to the air, however, the same wetness that had protected the bones made them soften and crumble, so that only a few of the more durable parts could be handled without falling to pieces. For this reason it is doubtful if more than a small portion of the whole skeleton can be recovered and reassembled. The deterioration of the fossil upon exposure is taken as evidence that the Colorado River had never before been so low at this point since the animal died there; because if it had ever before dried up to the point of exposing the bones, they would have crumbled then. Grover Moore, one of the owners of the land on which the discovery was made, found the relic several days ago while looking for fish in the pools along the river’s bed, which contained all the water remaining in the Colorado in that section. He found two ivory tusks, each about five feet long, protruding from the water at the edge of one of the pools. He also found a rib, about the same length or longer, three gigantic teeth, and two vertebrae, or backbone segments, nearly as large as the teeth. Two of the teeth were about as large as a human skull, though narrower. They were petrified or ossified, and well preserved, showing clearly the curving patterns of indentations on the grinding surfaces. All these things were found on the surface. Tusk Taken “I can’t imagine who got the tusk,” said Mr. Montague, “or how they got it up this steep bluff. It was nine inches thick at the base and must have weighed more than 100 pounds. But the tusk was gone, leaving only enough trace to show that it had been there. The rib too, was broken and mostly removed; so that the visitors realized that if they were to see any materials for pictures and descriptions besides the teeth and small bones they’d have to dig. Accordingly they set to work with spades, and at once discovered that anywhere they dug in that vicinity, their instruments struck bones. Some of the bones were so soft that the spades went right through them, laying bare the porous texture and brown color; others were partly hard and partly soft; but too unsubstantial to be dug up intact. One bone solid enough to be excavated was found, and it was a whopper. It was the femur, or thigh bone, the largest of the skeleton. It measured 4 feet and 4 inches in length, and at the ends was as thick as an average persons’ waist. From this bone and the length of the rib, and the size of the vertebrae bones found, and the teeth, Mr. Gustafson, estimated the size of the beast as already described. Others agreed with his estimates. Dislocated by Water The bones lay in the general position of the skeleton, but evidently had been somewhat dislocated by movement of the water and silt. Most anywhere within an area of about 30 feet in diameter the spade would strike bone just below the surface of the mud that formed the river’s bed; indicating that the entire skeleton was there. But digging down there in the blazing afternoon sun at the foot of a 40-foot bluff, was like digging into an active barbecue pit. An hour of it was enough to make any white collar man’s tongue hang out. After unearthing that one big one and a few smaller ones, the excavating party adjourned to cooler pursuits, leaving the rest of the job to more hardened laborers. This fossil has become the center of interest in Matagorda County, and a fascinating objective of speculation. How long ago did it live? What did it look like? Where did it come from? What did it eat with those enormous molars? What manner of human beings, if any, and what other kinds of creatures, were contemporary to this mammoth? Or was its day before the evolution of mankind upon the earth? These questions and others were asked by those who viewed the fossil remains as they wondered of the strange conditions that must have existed at one remote time upon this selfsame soil which they now tread in civilization’s well-paved path. Cause of Death Debated But probably the most puzzling riddle of all was, what became of the mammoths or mastodons that once plowed their way through the Texas forests, probably in mighty herds, trampling fair-sized trees like weed and grass in their headlong passage, trumpeting their calls and challenges like locomotive whistles? Not a single living descendant of the species has ever been discovered on this continent; nothing but their fossil remains. Were they wiped out by flood, or fire, or cold? No sure and definite answer to any of these questions can be given. They are the mysteries of the ages, buried by the all-obscuring hand of time. Only an occasional intimation can be gained by such discoveries as that at Bay City. One interesting thing about that mammoth is known: That when it became mired in the quicksands there, the river banks was about 30 feet lower than it is now. The observer can easily see the natural earth reaches its height and the upper strata of silt begin. This silt has built up the surrounding land to the level of about 30 feet higher than natural earth, making a bluff of river bank of some 40 feet, rising sheerly from the river at this place. It will be remembered that until a few years ago a vast “raft” of driftwood, logs, brush and silt congested the river the miles and miles in this section. The Colorado River raft in a way dammed up the river and created a great flood menace. Its removal from the stream in about 1927, was a notable engineering feat, publicly financed. Water 40 Feet Deep Before the raft was removed, he water stood normally up to the top of this 40-foot bluff, or nearly so; and the bones of our mammoth were covered by that depth of water. It has been suggested that the more active movement of the current, since the removal of the congestion, may have swept from those bones part of a deeper covering of mud, which previously might not have been exposed them to view even if the river had ever become as dry as it is now. This theory, however, conflicts with the fact that the river bed generally has not been deepened, according to those who know the stream. “I’ve lived around here for 50 years,” declared “Uncle Tom” Hightower, “and I’ve never seen the river so low.” Neither had D. P. Moore, father of Grover and Jerome, a pioneer who lived in Indianola in its heyday, and was the first postmaster at Elliott’s Ferry. While thus benefiting science by going dry, the Colorado is playing hob with the rice farmers of this section, where rice growing is a major industry. They depend upon the river for irrigation, but not there’s not enough water in it to pump. “If it doesn’t rain soon,” declared Mr. Gustafson, “this low river is going to cost our rice farmers $1,000,000.” So you might say, in a sense that the Bay City mammoth discovery was made at a cost of $1,000,000! Editor’s Note: After this interesting article by Mr. Kilman was published the rain came to the extent of about six inches in four days time, saving the rice crop. The Tribune takes this opportunity to thank the Houston Post for this splendid article and the splendid work accompanying it.

Matagorda County Tribune, Thursday, August

3, 1933 |